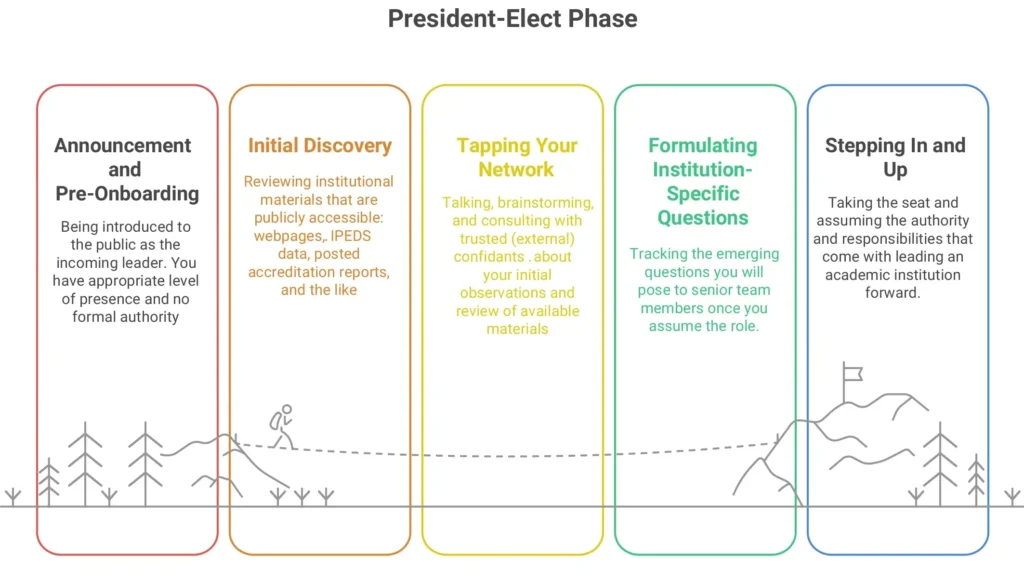

Phase 1. President-Elect—“I Don’t know you; You don’t know me”

Timing

This phase starts the moment the university announces its new president and ends on the first day the new president officially takes the seat.

Description

This is the behind-the-scenes, early discovery stage. Without formal authority, you make no official decisions and respect the fact that a university has one president at a time—and it’s not yet you. Conversations you have with soon-to-be colleagues should be cleared by the sitting president and, perhaps, the board chair. No meetings should be arranged behind the current president’s back.

Common Activities

As part of the initial discovery phase, you review publicly available materials: websites, social media platforms, alumni magazines, recent and past “news” posts, and the like. Additionally, you are apt to request copies of budget reports and forecasts, accreditation reports, enrollment strategies, fundraising metrics, bond or debt summaries, collective bargaining agreements, climate surveys, and similar.

If you are fortunate enough to have a Presidential Transition Partner, they can assist in reading, reviewing, and annotating these documents.

Keep a list of emerging questions and issues that will guide conversations with the senior team once you take the helm. These questions and their answers should help reveal where the institution is strongest and where it is most vulnerable.

Real-Life Example

In one case, a president-elect inherited an institution under heightened accreditation scrutiny. With an external peer team scheduled to visit campus within the first 60 days of her tenure, the president-elect read all recent internal and external accreditation reports, familiarized herself with the accreditation standards of that particular commission, and began mapping out possible areas to highlight during the imminent campus visit.

Phase 2. The New President — “Getting to know you, getting to know me.”

Timing

This phase typically overlaps with the first 12–18 months in the role. But in some cases, the incumbent is still viewed as the “new” president for two full years or so.

Description

Often, this is the sweetest phase of all—some even call it the “honeymoon period.” It is generally marked by goodwill and curiosity: you are giving internal and external constituents the benefit of the doubt, and they are extending the same generosity to you.

Common Activities

Within your first ninety days, you will likely embark on a learning and listening tour coordinated by your Onboarding Staff and Presidential Transition Partner, if available. This tour allows you to get out and about, meeting a broad swath of campus and community constituents.

You visit faculty and staff in their own spaces and places (including remote ones), giving them a chance to tell you a story or ask a question. In turn, this allows you to respond with emerging observations and early answers that communicate your interest and awareness—without prematurely committing you or the institution to actions you’re not yet ready to confirm.

You will also attend receptions, lunches, and socials with internal community members, donors, alumni, parents, and community VIPs. It’s wise to have a “knowledge escort” walk you around the room, making introductions and helping you connect the dots between established interests and potential impact.

Most new presidents use the first 12–18 months to assess their direct reports. At universities where significant change is required, the president must have a team of senior colleagues willing and able to not only support but also lead the anticipated transformations.

Real-Life Example

During one presidency, I spearheaded a boutique fundraising campaign to create a “Possibility Fund.” This fund awarded small grants ($500–$2,500) to faculty, staff, and students who proposed high-impact, low-cost improvements to university life. It was a meaningful way to reward creative ideas and log in a few early wins.

Frequently Asked Questions

What should a university president-elect focus on before officially taking office?

The pre-start period is about listening and learning, often from afar. This is not the time to make any decisions. A president-elect should focus on understanding content and context. This means you will review available documents, websites, alumni magazines, news stories, and the like. The goal is to build a foundation of awareness so you are not coming in cold.

How does a president-elect balance curiosity with respect for the sitting president?

It requires following the leader and taking your cues directly from the sitting president. Some departing presidents are ready to fold their successor into a few meetings here and there; others want their “replacement” to stay away until it’s their turn at the helm. You stay on the side until you are invited onto the stage, and you enter at the pace set by the director: the sitting president.

What are the most important documents to review during the transition phase?

Start with the strategic plan, accreditation reports, financial statements, enrollment scenarios, and board meeting minutes. You’ll also want to look at collective bargaining agreements, donor agreements, and campus climate surveys. These documents reveal the institution’s priorities, pressure points, and promises.

Why is it critical for a president-elect and new president to keep a list of emerging questions?

Writing down questions helps you track themes across conversations and documents. It shows stakeholders that you’re paying attention and provides a running list to revisit as you learn more. It also prevents premature commitments while keeping curiosity alive.

Can a president-elect meet with faculty and staff before their official start date?

Yes—if it’s done in coordination with the sitting president. Visiting people in their own spaces, including remote settings, gives them a chance to tell you their stories. In turn, you can share early impressions without overstepping. These early encounters build goodwill and ease your transition.

What is typically expected of a university president in their first 90 days?

The first 90 days are about presence and engagement, not sweeping changes. Trustees, faculty, and staff expect to see you listening carefully, showing up at key events, and reflecting back what you’ve heard. You’re setting a tone of commitment, respect, and readiness to lead.

Why is the first year of a presidency often called the “honeymoon period”?

Because the level of goodwill is usually higher in early stages than later ones. Most Constituents want to extend a warm welcome to the new leader and help them succeed. Most new presidents are given grace for their early missteps. But the honeymoon does not last forever. It’s wise to use this window to build trust, log a few visible wins, and create momentum before the harder decisions come.

How can new presidents build trust with faculty, staff, and students?

Trust is built through consistent presence, predictable follow-through, and genuine care for the human being. That means showing up at events, being transparent in communication, and closing the loop on commitments. Even small gestures—handwritten notes, quick replies, or walking across campus with someone—signal that you care.

What role do receptions and community events play in early leadership?

These gatherings are essential for relationship-building. Attending receptions, lunches, and community events shows stakeholders you value them. Having a “knowledge escort” with you can help connect the dots between names, issues, and opportunities. Each introduction is a chance to make a connection on a shared need or interest.

How should a new president evaluate their senior leadership team?

Most presidents use the first 12–18 months to assess their cabinet. At institutions facing major change, it’s critical to have senior leaders who not only support your agenda but also actively lead transformation. Look for alignment with institutional values, willingness to collaborate, capacity to execute, and courage to speak truth to power.