Introduction

A version of this blog post was also submitted to The Chronicle of Higher Education in response to the article, The 774 Words That Helped Sink a Presidency in the May 7, 2025 issue of The Chronicle.

Full disclosure: I’ve known the former President of Cal Lutheran University (CLU), Lori Varlotta, for most of my professional life in higher education. I worked with her at my Alma Mater, California State University, Sacramento, where she was VP of Student Affairs; consulted on two short-term projects for Hiram College when she was President there; and kept in touch with her since. In a phone conversation in the last 18 months or so she mentioned she was facing challenges in her then-current Presidency at CLU. She didn’t go into detail—we had plenty else to catch up on—and I thought little of it: senior administrators face challenges constantly.

Very recently, Dr. Varlotta’s challenges at CLU were the subject of a highly substantive article published in the Chronicle of Higher Education. The article, peppered with quotes and passages from primary sources, prompted me to learn more: not only because of my connection to and respect for Dr. Varlotta, but because of my interest in campus governance and politics. I’m an English professor who has served in department- and campus-wide leadership roles. Though I am no expert in the aforementioned issues, I try to stay informed.

After reading the attachments linked to the Chronicle article, accessing some of the court documents, and perusing the articles and letters published by the local press, I thought of my students. Immediately, conversations I’ve had with them when campus controversies are covered in the student newspaper came to the forefront of my mind. When something is happening on campus and part of the story seems missing, I ask my students: “Where is the pressure coming from?”

Asking that question myself is how I got curious with the situation involving Dr. Varlotta stepping down from the CLU presidency: where did the pressure come from? As you’ll read here—as you can deduce for yourself from many publicly available materials, as I did—the answer to “whence the pressure?” is clear, and to me, disturbing. When I heard Dr. Varlotta was facing challenges at CLU, I expected them to be run-of-the-mill: budgetary, perhaps based on enrollment or tuition or fees, perhaps focused on where to make cuts, perhaps ideological related to all that, but certainly with students at the center.

Not so.

In “unpacking” this saga for interested readers, I draw heavily from (and attach) two resources: the PowerPoint used by CLU’s attorneys in their closing argument (Varlotta is one of three named “defendants”) and an Exhibit containing emails, letters, and other communication obtained via the court discovery process. I found these and other court “data” fascinating.

Summary of the Gallegly Case

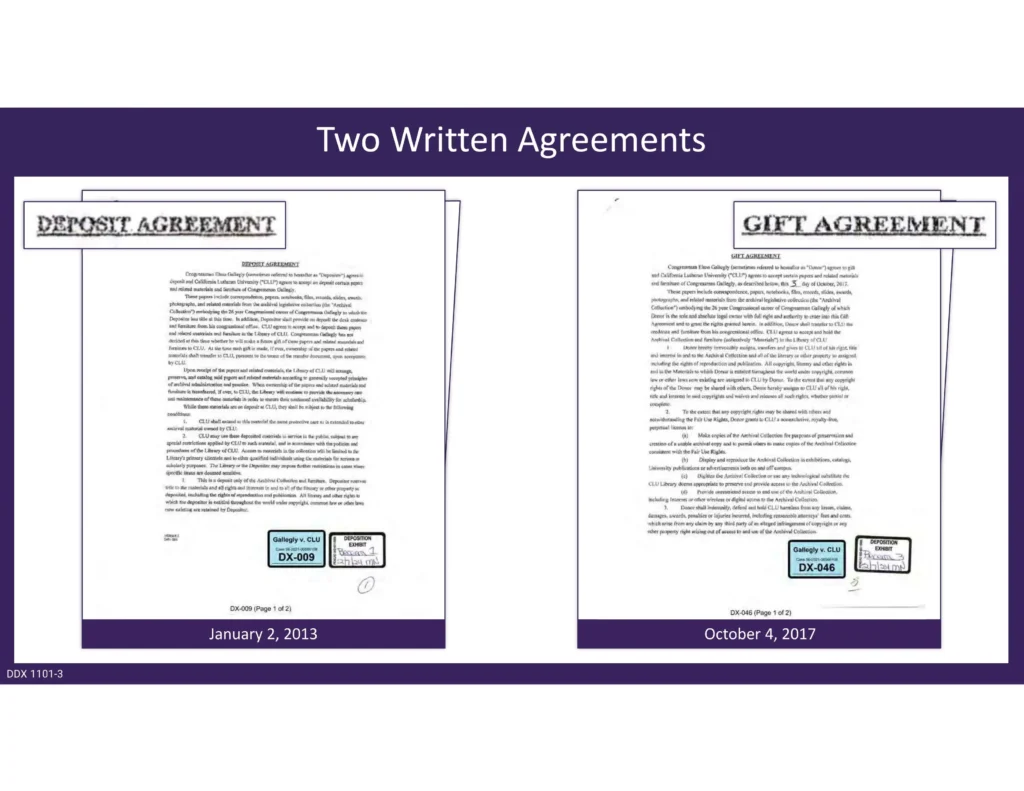

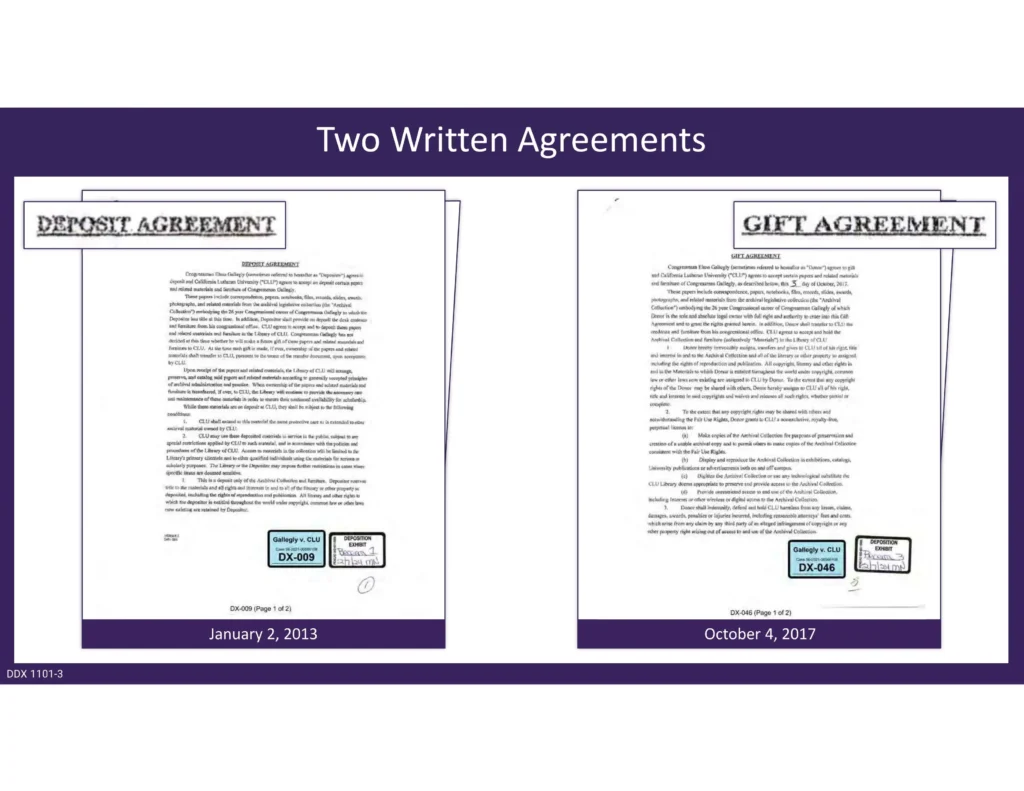

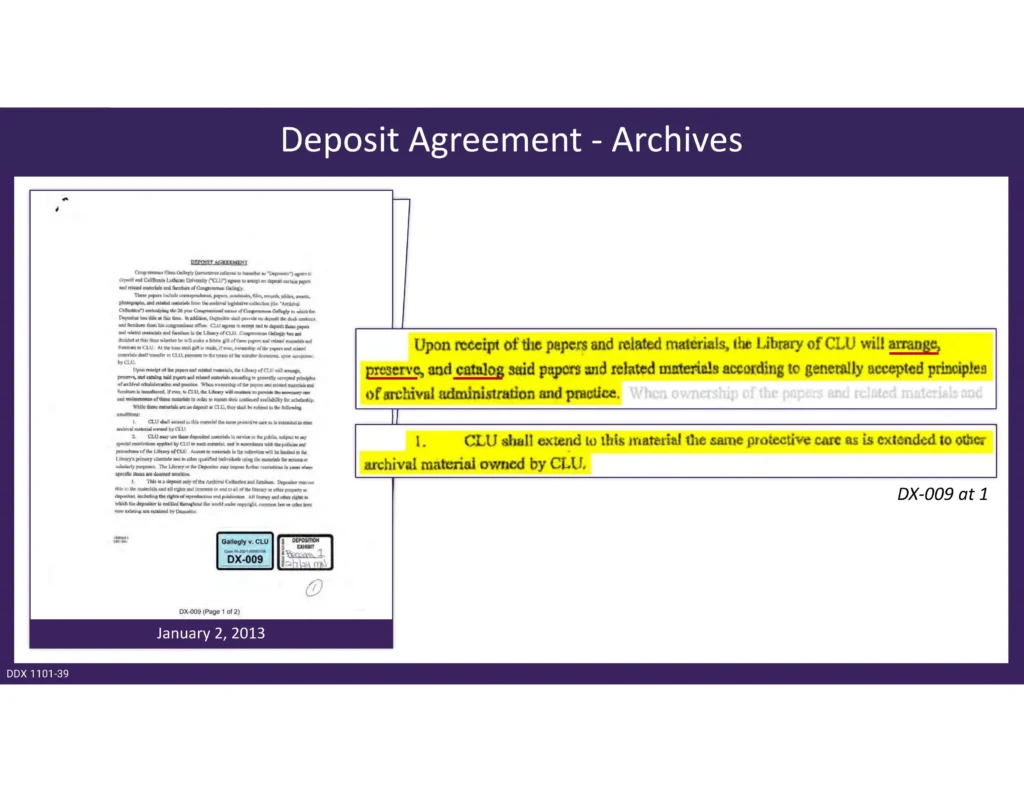

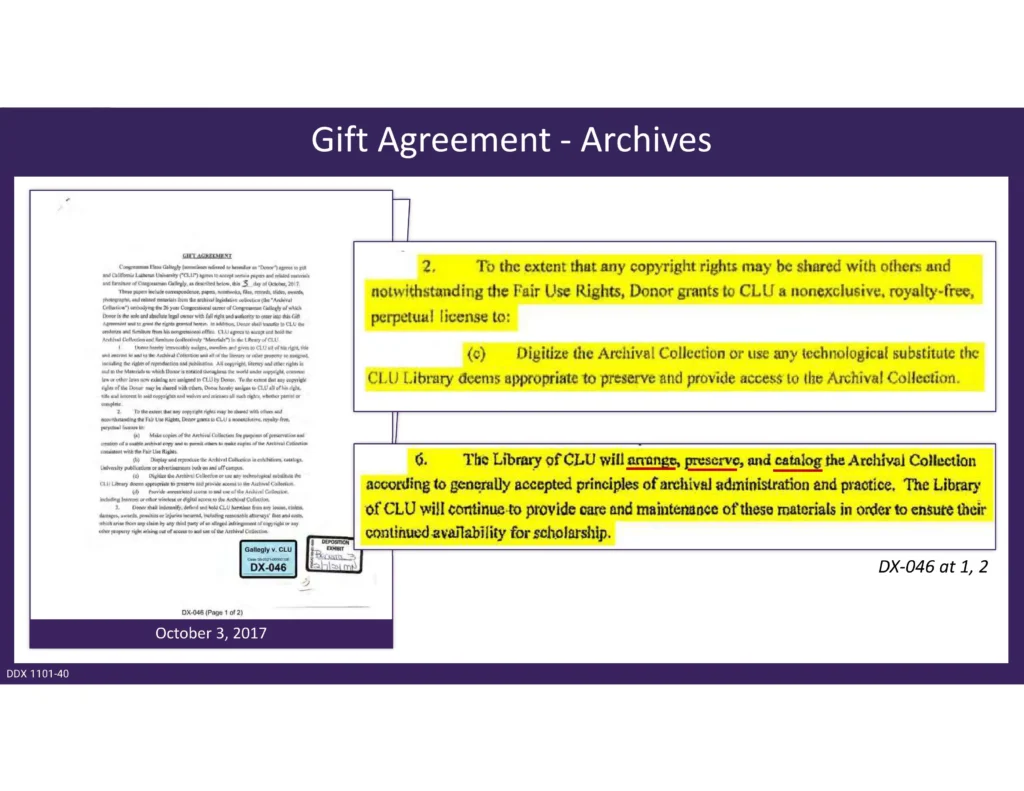

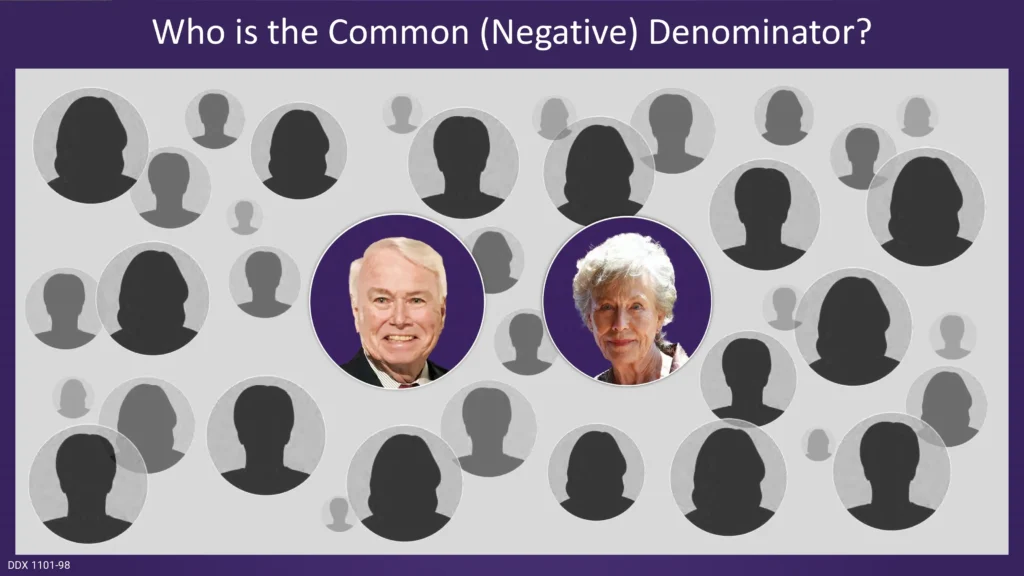

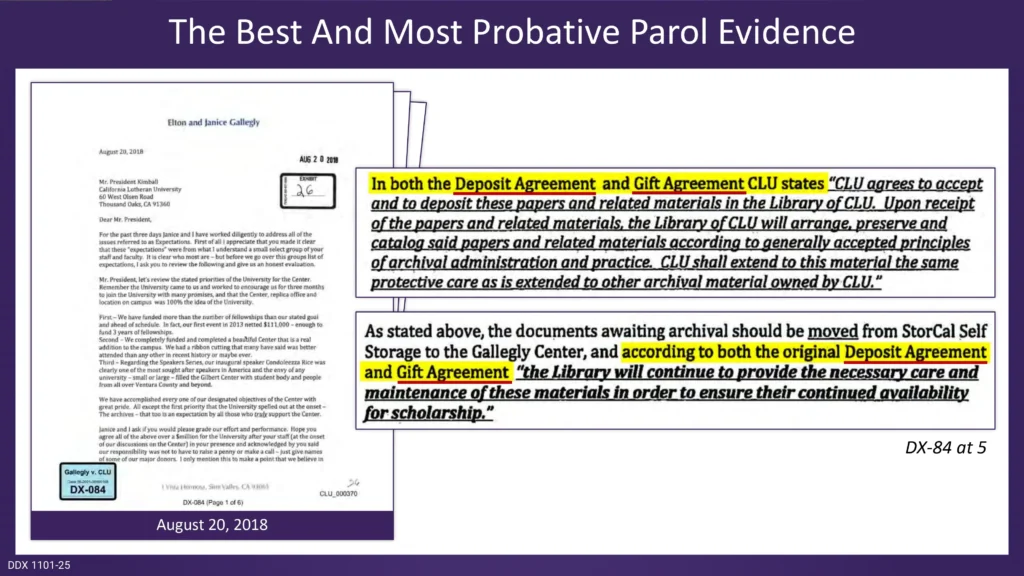

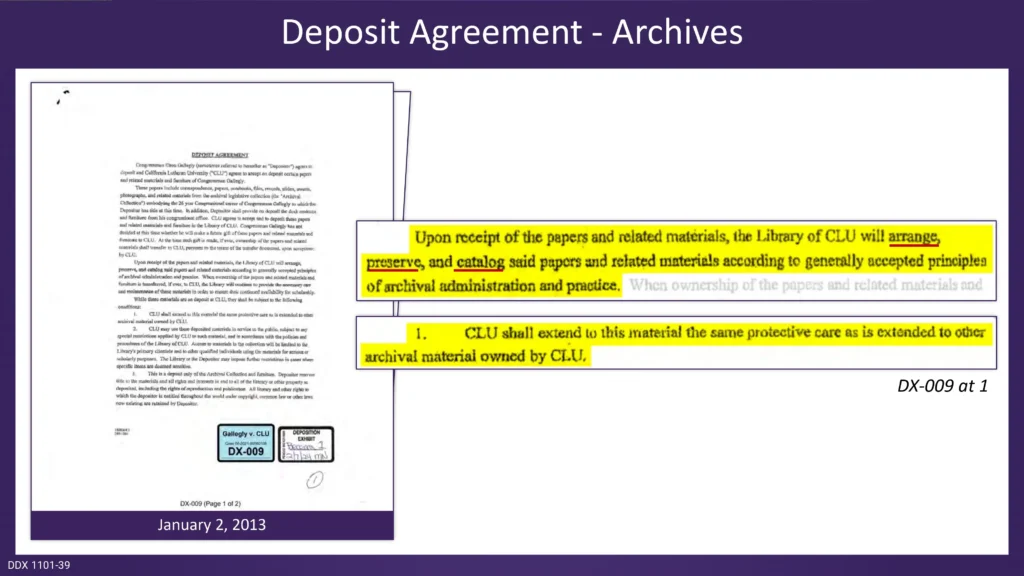

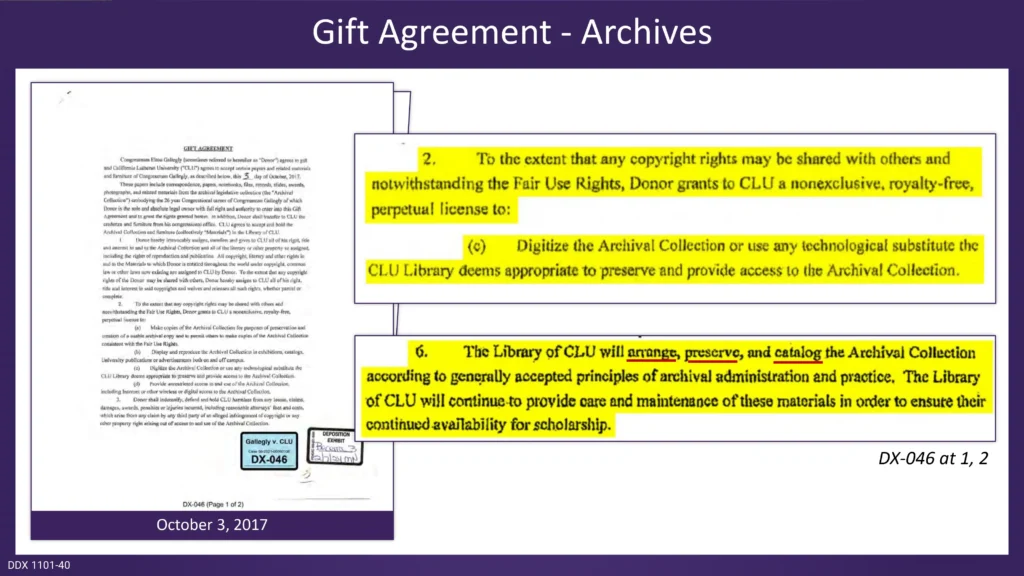

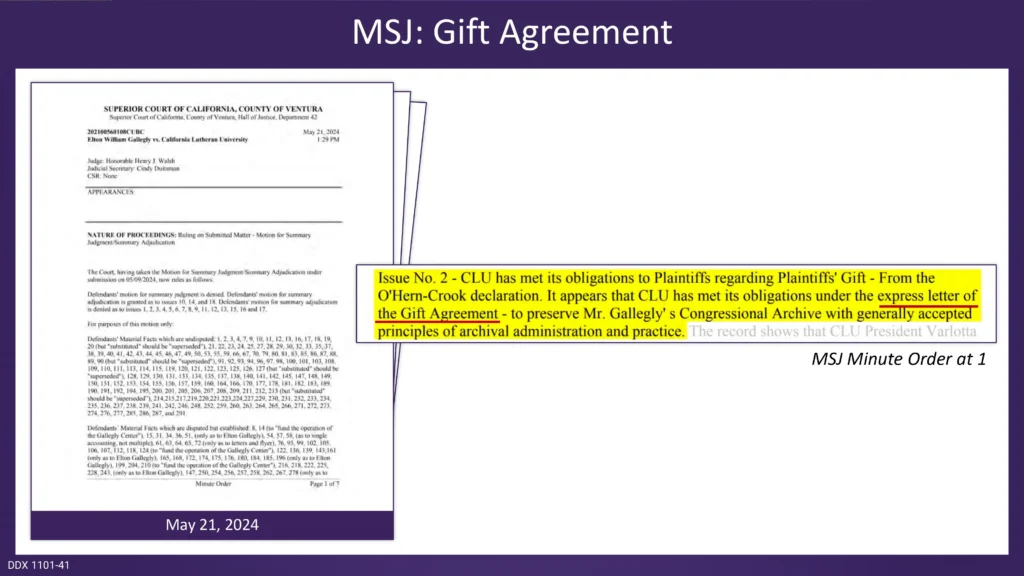

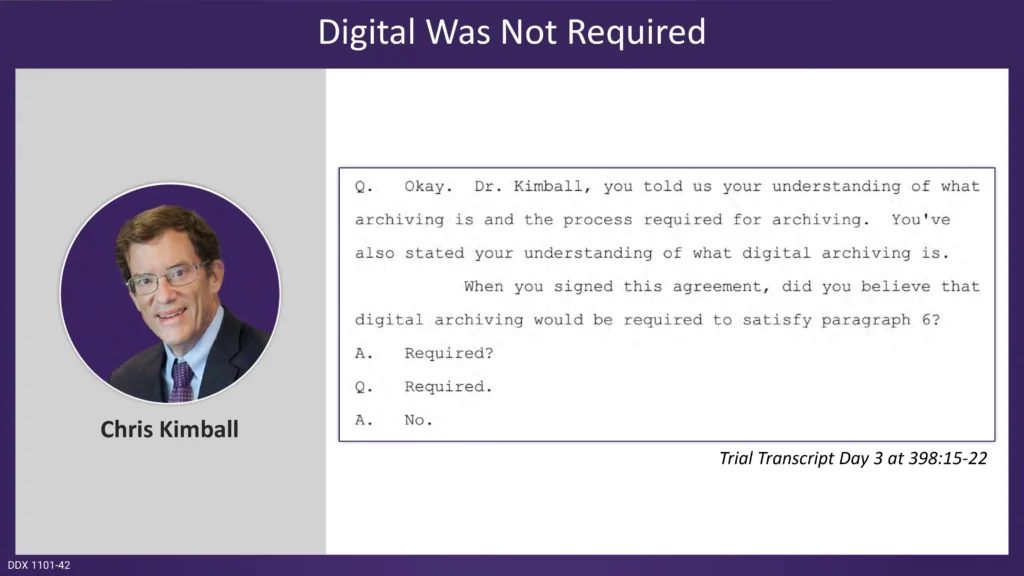

Dr. Varlotta became the central target of a multimillion-dollar legal case that former Congressman Elton Gallegly and his wife, Janice, waged for four years against the small, private institution in Thousand Oaks, CA. At the heart of the lawsuit is the claim that CLU is contractually obligated to display a replica of Galleglys Washington, D.C. office and to digitize his congressional papers, neither of which are required by the underlying agreements (see slides #3, 7, 39, and 40 in the Defendants’ Closing Argument Presentation, or DCAP).

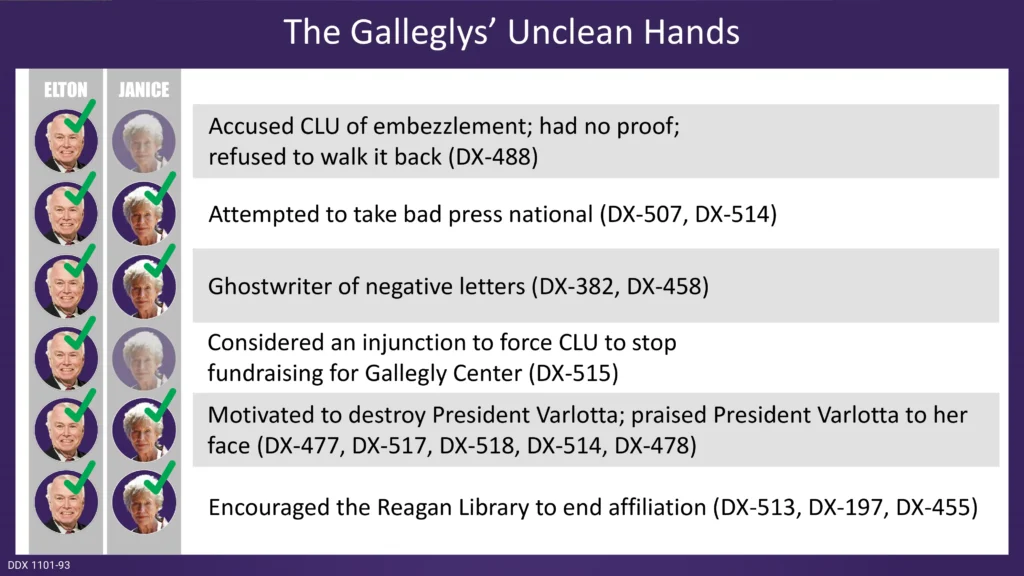

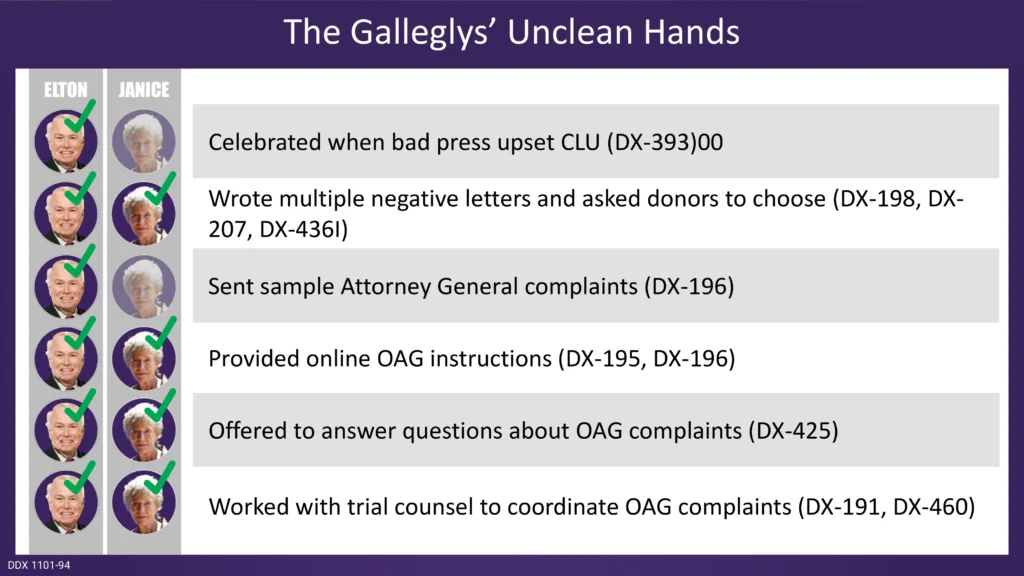

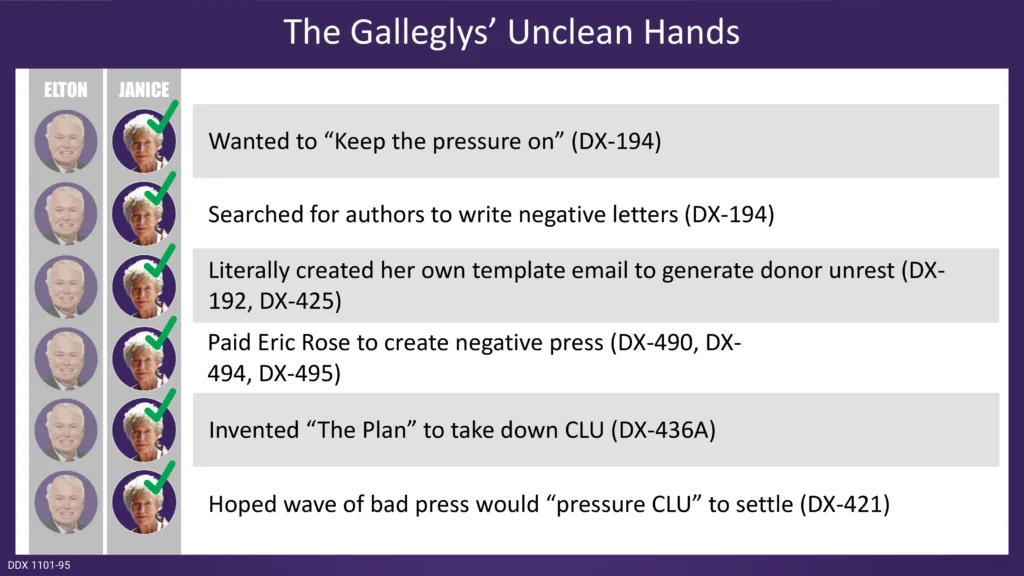

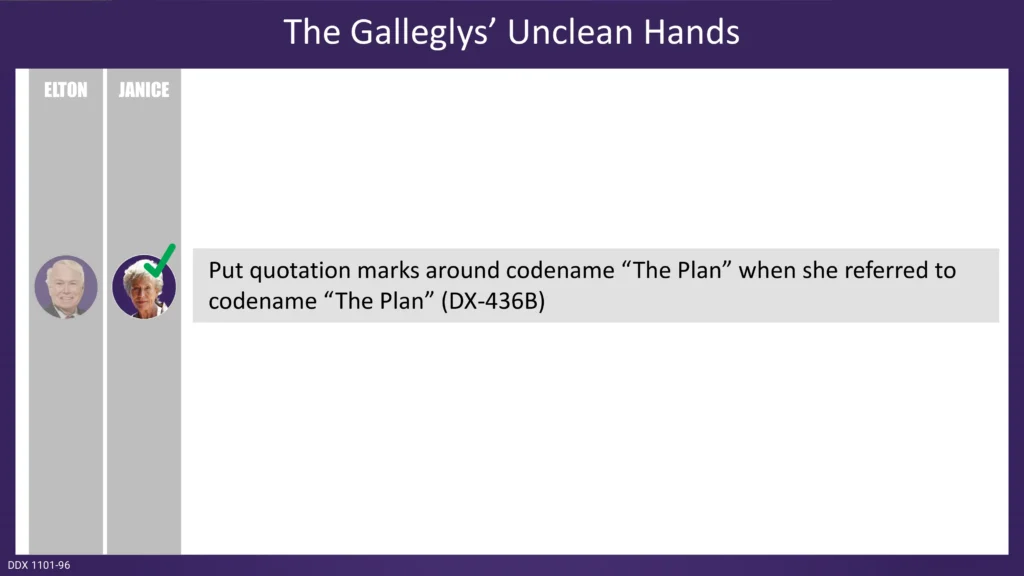

Testimony and court documents provide evidence that the Galleglys worked to turn the court of public opinion specifically against Dr. Varlotta. For more than three years, the Galleglys and their associates maintained a smear campaign to pressure the university into meeting their demands and to discredit its leaders for refusing to do so (see DCAP slides #91–98 and Exhibits 1–18 in the Combined Exhibits file).

The Gallegly Center and Its Programs

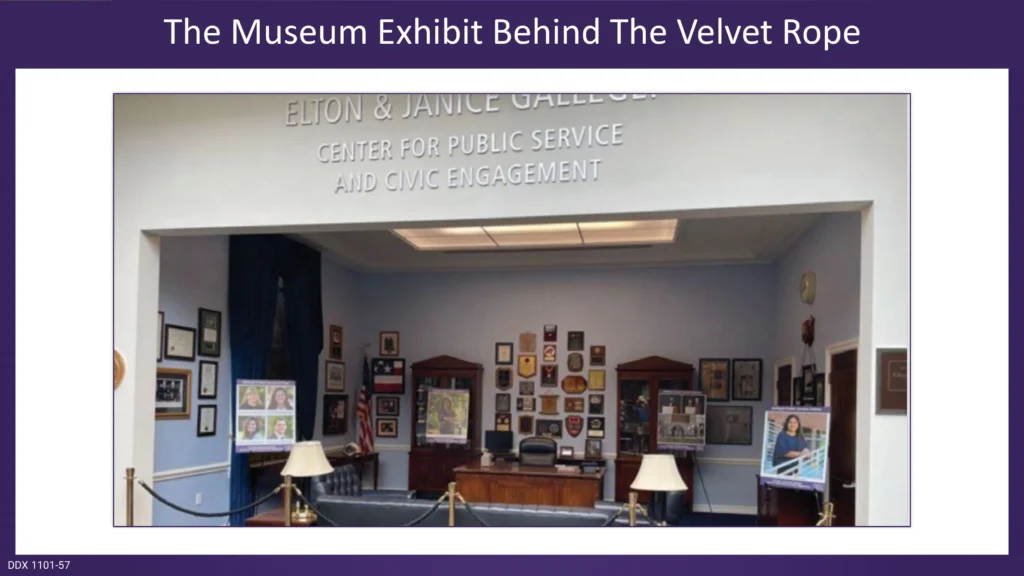

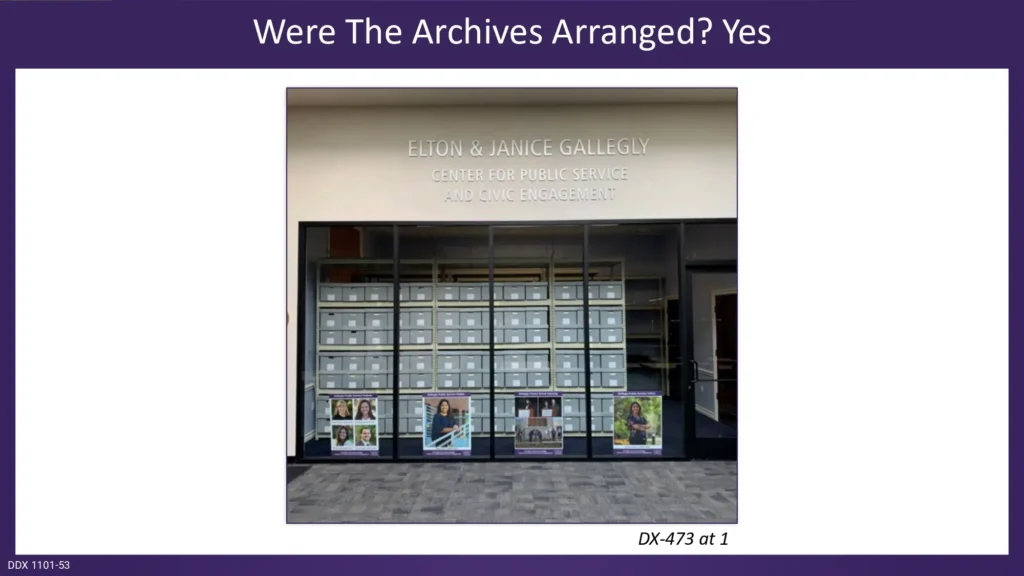

In 2018, CLU constructed a 1,500-square-foot annex to the University Library to house the Elton and Janice Gallegly Center for Public Service and Civic Engagement. The facility, built at a cost of approximately $600,000, was largely funded by one-time gifts. For the first few years, it included a replica of Galleglys Washington, D.C. office on display (DCAP slide #57).

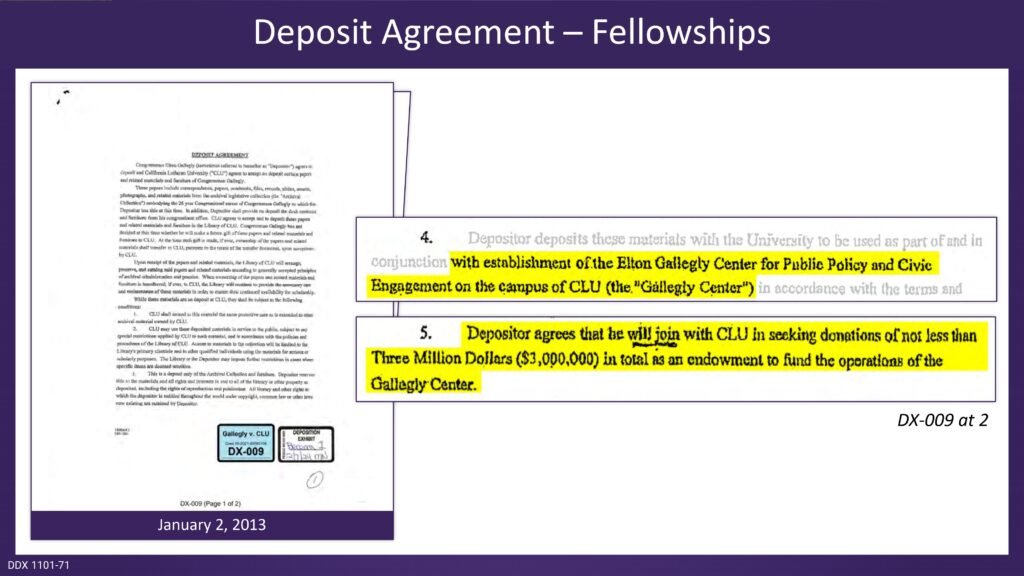

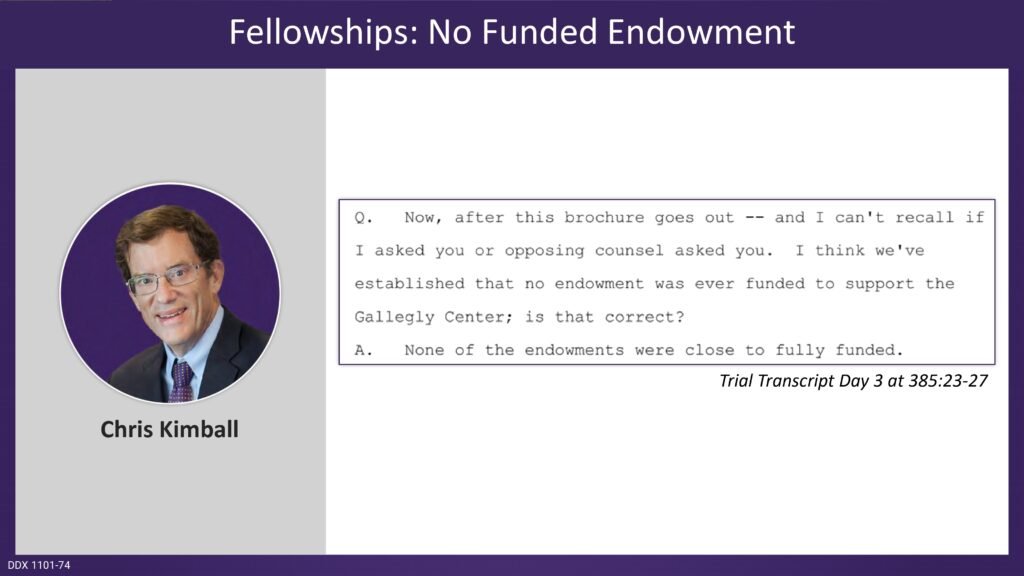

From the start of the relationship with CLU in 2013—which long predated Dr. Varlotta’s tenure at the University, which is obvious but worth noting—the Galleglys had pledged to help raise at least $3 million to offer and endow the Center’s programs. The proposed programs included a speaker series to foster public discourse and a fellowship program to attract high-caliber students to CLU’s Master of Public Administration program. The endowment was intended to cover the speakers’ series and fund tuition for the fellows (slides #71, 74, and 76). No endowment funds were ever raised.

Office Comes out; Archives Go In

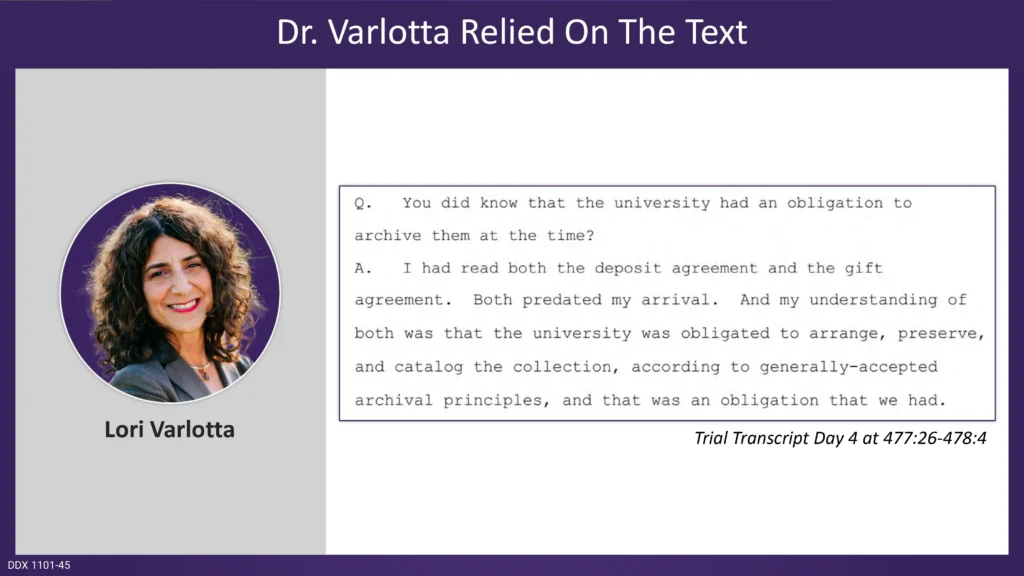

With no funding in place and Gallegly Center programs paused, university leaders jointly (slides #58-60)—not Varlotta unilaterally—decided, in 2021, to remove the replica office. The space that formerly held the furniture was repurposed to safely house the 450-box archival collection donated by the Galleglys (DCAP slide #53). This decision was made to comply with the two contracts signed by university and the Galleglys in 2013 and 2017. While the contracts explicitly mentioned preserving and cataloging archive materials, neither included a single mention of a displaying any replica office.

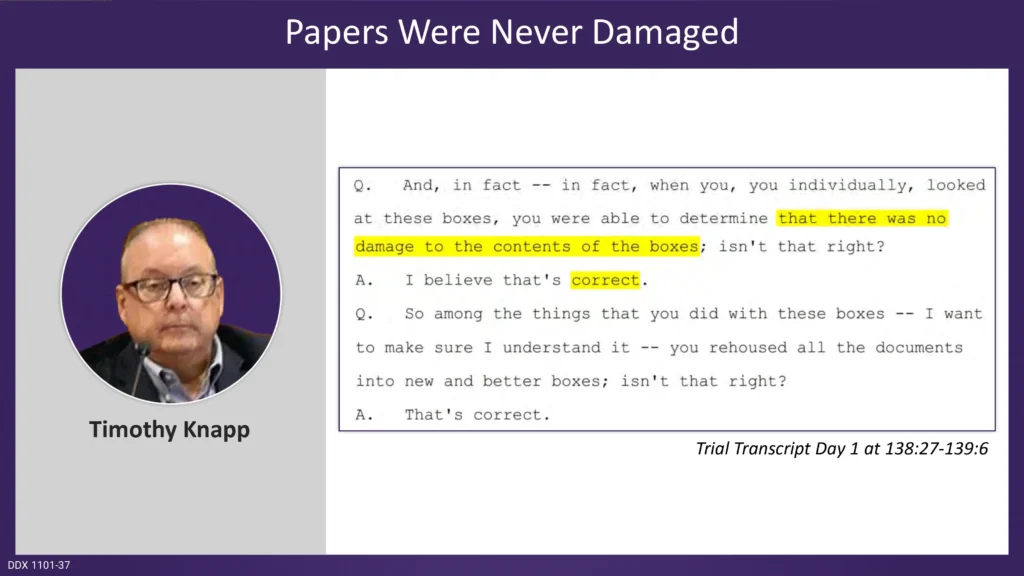

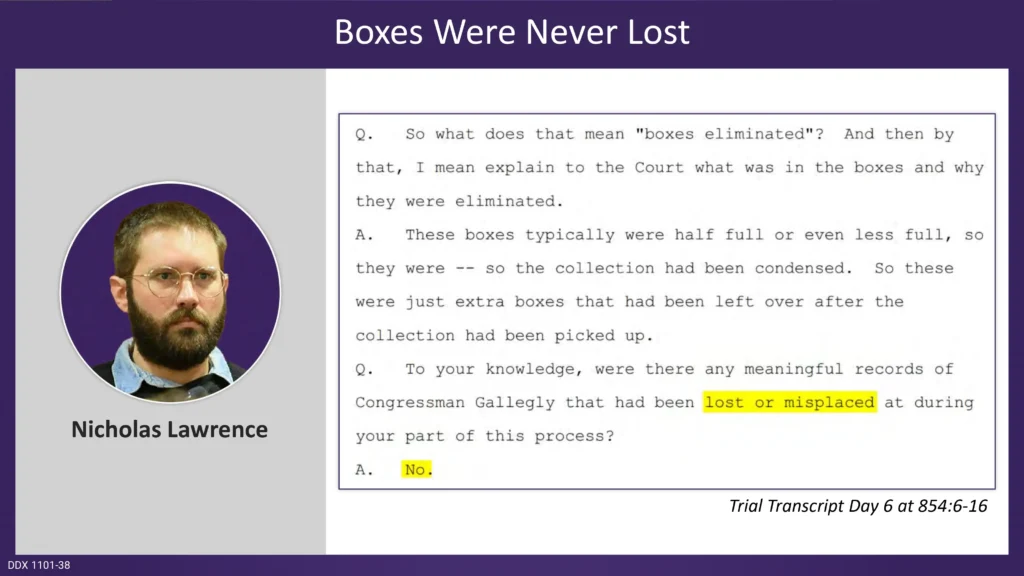

During the first phase of the trial, witnesses for both parties testified that the moves the university made were directly in line with its contractual obligation to preserve, catalog, and maintain the collection for scholarly use (DCAP slides #25, 37–47). But the Galleglys own archival expert goes one step further. Under oath, he states that the former “office space” is the most appropriate location for the collection (slide #61).

Since its installation, the archive has been made fully accessible to students, faculty, and researchers, although few, if any students have accessed it for research (slide #53).

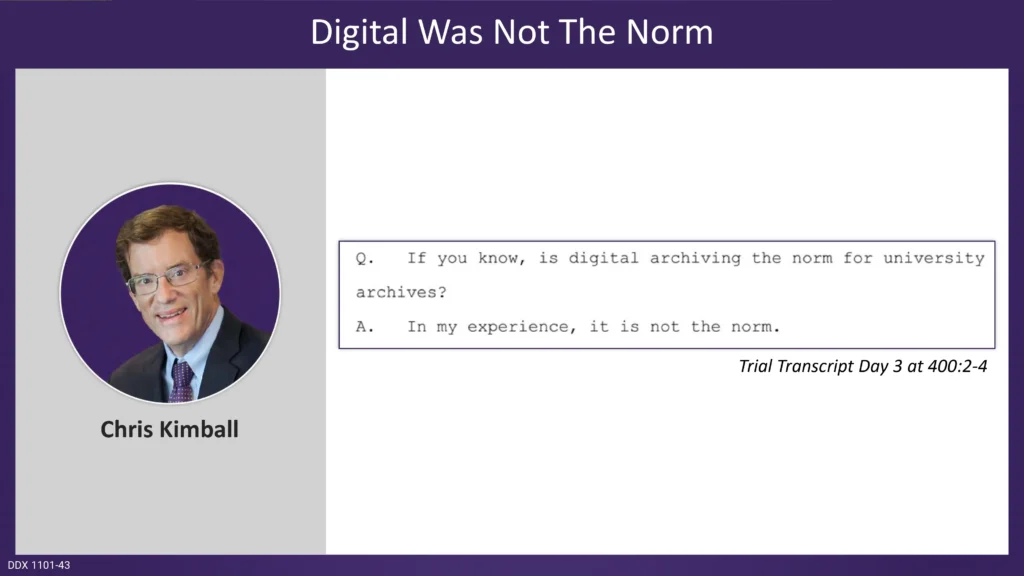

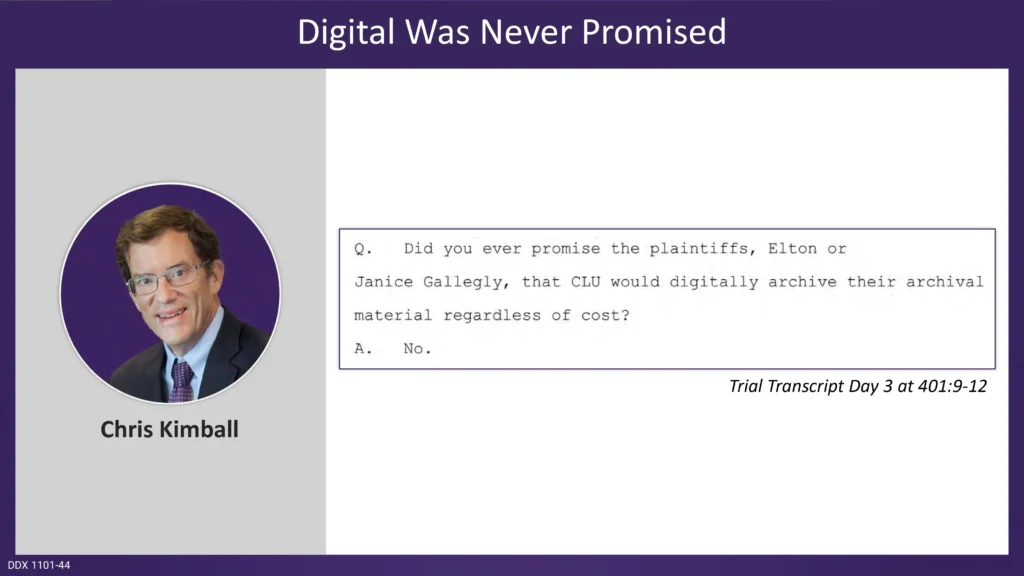

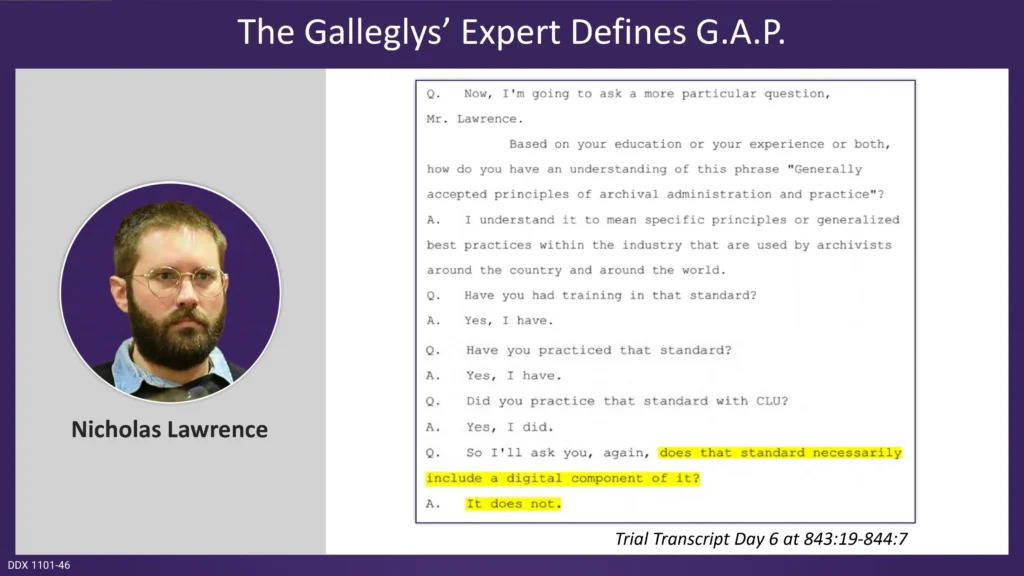

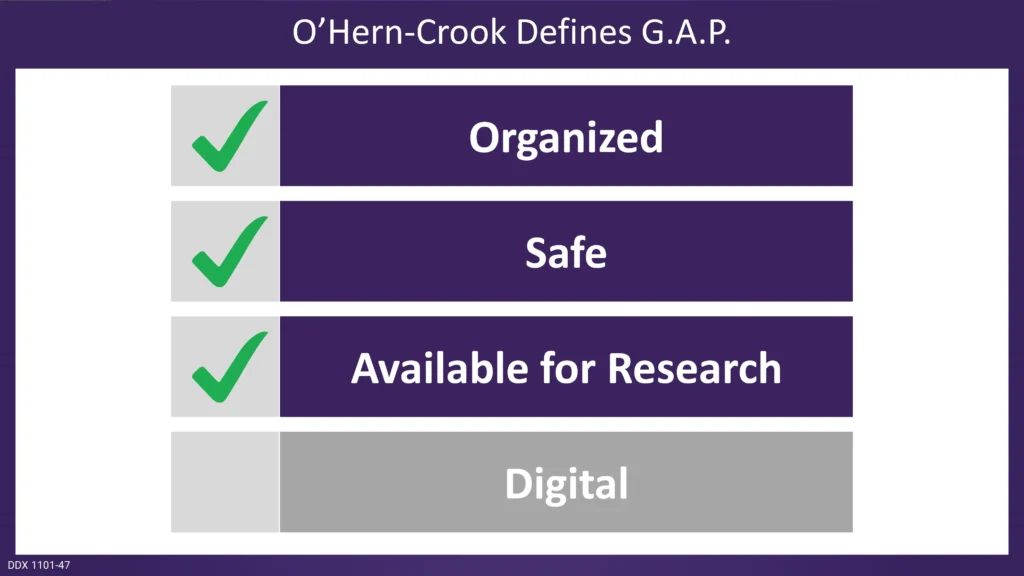

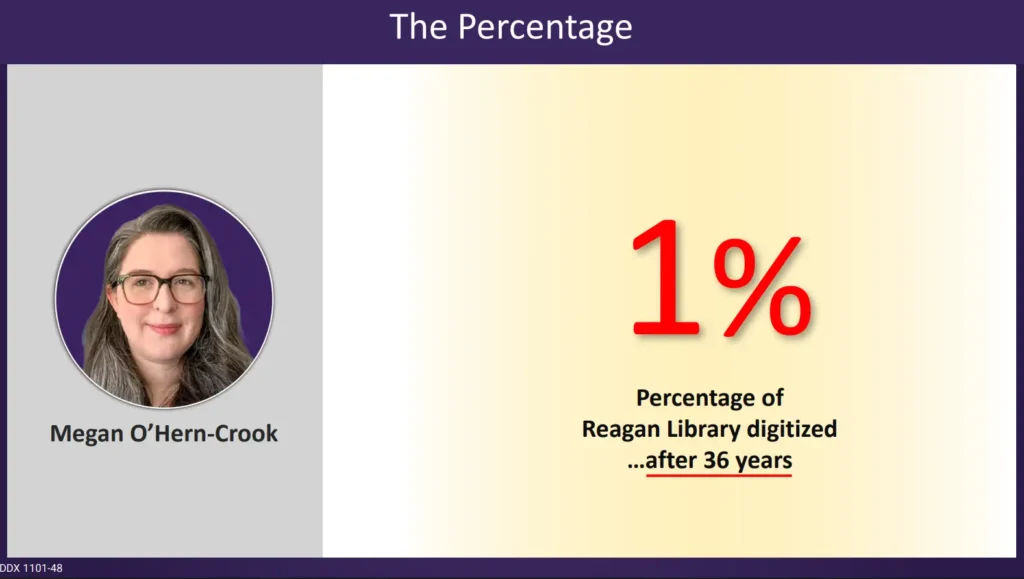

The Push to Digitize

Despite the physical archive being preserved and accessible, the Galleglys insisted that the university digitize the entire collection—yet another demand that was never promised or contractually required (slides #42–44). Although lack of contractual stipulation is one reason for not having digitized the collection, equally important is a more straightforward factor: cost. Digitizing such archives is expensive. As an example, during the court proceedings, a presidential library expert testified that after 36 years, only 1% of Ronald Reagan’s papers have been digitized, underscoring how unreasonable it would be to expect a small private university to digitize a congressional archive of this size (DCAP slide #48).

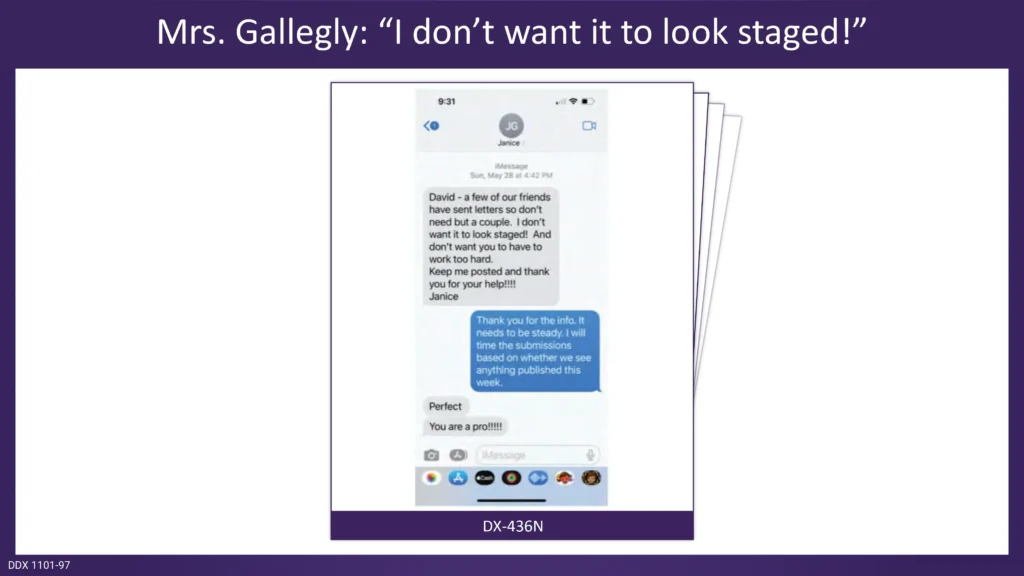

A Misinformation Campaign to Influence Public Opinion

Because of their dissatisfaction with the university’s moves, the Galleglys engaged two heavy-hitting PR firms and a group of volunteers in a three-year letter-writing and media campaign. The Galleglys and their associates convinced dozens of supporters to sign their names to and submit letters containing misinformation and unfounded accusations to local newspapers. In addition, unsubstantiated complaints were filed with the California Attorney General’s office, alleging that CLU had committed not only a breach of contract, but a “breach of trust” with the Galleglys. This notion of a “trust” is a complicated legal issue, but the court has sided with the defendants and found that there is no trust, and hence, no breach of trust in this case. After reading the tome of court documents, it would be difficult to argue against this conclusion: the campaign was meant not only to influence but to mislead the public by providing partial information and making unfounded accusations against the university and its president (see Exhibits 1–18). What the Galleglys asked solicited letter writers to sign their names to differed from what the Galleglys stated under oath.

The court documents reveal, in no uncertain terms, that the criticisms by the Galleglys and their supporters’ were directed mostly at Dr. Varlotta—the first female president of CLU. She assumed office in 2020, years after the contracts associated with this case were signed. Nonetheless, she was the focal point for their attacks. Testimony and emails show that Janice Gallegly, along with a group of volunteers—James Lacey, David Shechter, and Kevin McNamee—worked to undermine her leadership from the start. Attached emails confirm that this group worked tirelessly to create such a negative community buzz that the Board of Regents would fail to inaugurate their first woman president (Exhibits 14–17).

A President Steps Aside

After enduring years of an intentional and sustained campaign to damage her credibility—with the collateral effect of making most of the other parts of her job all but impossible—Dr. Varlotta stepped down as president in May 2024. Her decision was made in the interest of the university following a period during which the campaign’s impact on her reputation became too great to ignore. She continues to serve the university as its Distinguished Professor of Higher Education Leadership.

Institutional Damage

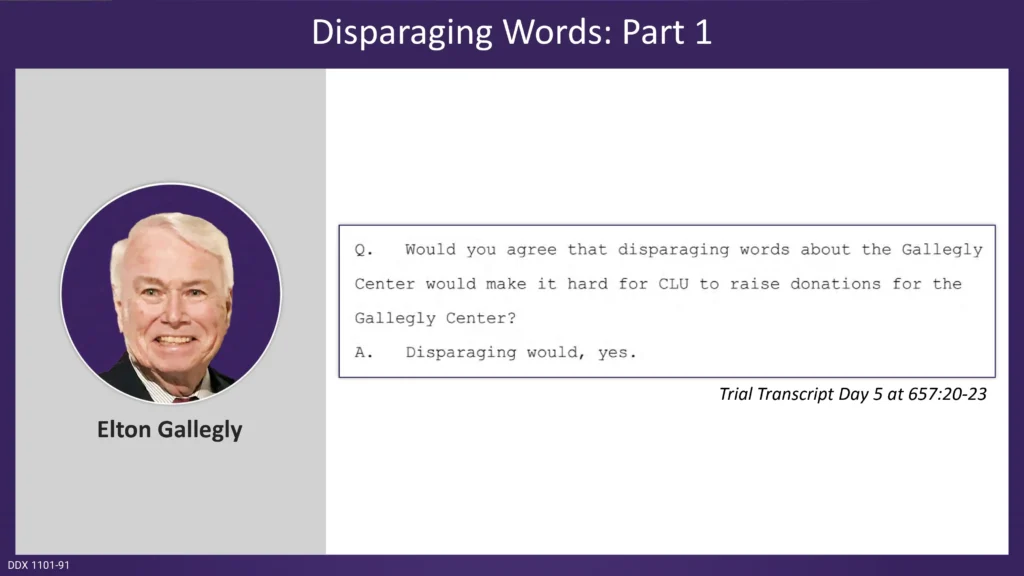

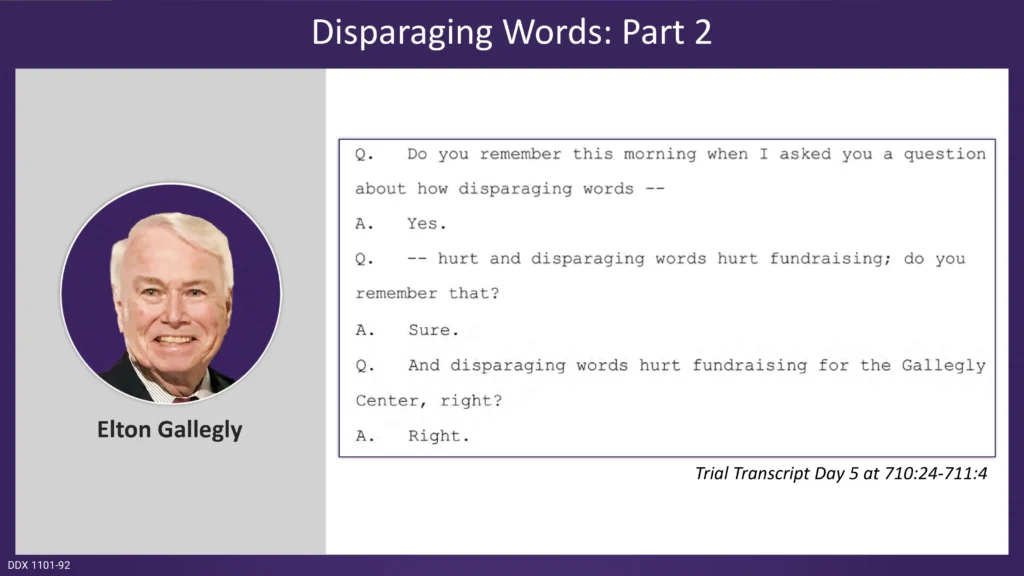

The damage extended beyond Dr. Varlotta. Even Elton Gallegly himself acknowledged that the public campaign negatively affected CLU’s fundraising efforts (DCAP slides #91–92). Records from public relations firms estimate that just one phase of the negative campaign against Dr. Varlotta and the University reached over 14 million people. The prolonged legal battle has cost the university and its insurance providers millions in legal fees and administrative expenses. The cost of the reputational damage is impossible to calculate. And so far, no one has made any attempt to address those damages.

A Cautionary Tale for University Fundraisers

The consequences of this case offer a cautionary tale for advancement professionals in higher education. As private colleges and public universities across the country increasingly look to donors to offset shrinking revenues, it seems necessary for them to weigh the benefits and risks of all potential gifts. It also seems prudent for advancement staff to be wary of donors who want a lot of strings attached to the gift or repeatedly change their mind about what a successful partnership looks like. Universities might even consider “out clauses” in case a donor’s expectations evolve into demands that are neither grounded in legal agreements nor feasible to meet. When legacy-building becomes a driving force, as it appears to have been the case with Elton Gallelgy, the result can be conflict that diverts attention and resources away from students and a university’s mission.

I would not be writing this article if the reputation of a friend and colleague wasn’t damaged so unjustly by all of this: all of this, which is ridiculously ancillary to any University’s mission, especially at this moment in higher education in America. Yes, there are lessons to be learned. University and donor expectations must be aligned and codified; any changes in expectations must be officially captured, recorded, and agreed upon so that newcomers to the university are not left in the dark. There appears to have been major mistakes made in these areas that predate Dr. Varlotta’s presidency. She was the one, however, who paid the price for them. Hence, this story illustrates something much more concrete than contracts and donors: the personal damage and institutional fallout that can result when individuals bring power to bear. “Pressure” equals “power” in this story. It seems likely this pressure won’t resurrect a replica of a 1987-2013 Washington D.C. office, nor send a score of PDFs to a cobwebbed corner of a library server.

Beyond Fundraising—Life Lessons

I have contemplated using this situation as a real-life case study in one of my first-year composition classes. I would ask students to comb through the publicly available evidence before arriving to or articulating any conclusions. Then, I would expect at least a couple observant, grounded students to ask questions about the materials, especially the many letters to the editor published in the local newspapers. They might ask: “Why did so many people buy into this? How come no one asked, at least publicly, what is the truth in this case?”

Surely, educators would agree that those are good questions. The entire media campaign—and much regarding the allegations of the plaintiffs—telegraph an agenda rather than a pursuit of truth. The court materials show that the agenda was “supported,” repeatedly by opinions, misinformation, and incomplete understanding of the issues. At least, I hope they were those things, and not conscious lies.

Rumor mills fueled by political supporters helped produce these poorly-founded opinions and arguments, gave them currency, and spread them. But what is even more troubling is that members of a university community seemingly allowed the disregard for the truth (or even curiosity) to proliferate. It is disheartening that in this CLU case, not even members of academia and those close to it sought to pursue, publish, and prioritize “truth” over accusation, opinion, and personal ego.

We live in a world where garnering e-story “hits” and social media “likes” draws readers in. But such responses are not the measures of effective University operations and governance work. University faculty, staff, administrators, and board members should hold ourselves to a higher standard of engagement; we must model ways to inquire about and investigate complex situations so that we are informed agents not reactive pawns.

Legal Outcomes and Lasting Impact

In December 2024, after reviewing extensive evidence, the trial judge in Ventura County reversed an earlier position and delivered a significant win for CLU in the first phase of the trial. Around that same time, Dr. Varlotta requested a public apology from the Galleglys, James Lacey, David Shechter, and Kevin McNamee for the reputational harm they collectively inflicted via their media campaign. None of them agreed to that request.

The next phase of the case is scheduled for jury trial in Ventura County Superior Court in the summer of 2025. Even if another court “win” is delivered to Varlotta and CLU the damage of the pressure applied by the Galleglys and allies is not easily undone.

Alan Haslam

Faculty -English